Ruins and artefacts of abandoned towns and villages, commonly labelled as ‘ghost towns’, can be found all across Tasmania, however mostly on the west coast and far north-east. Some are victims of boom-and-bust mining days, when the fortunes of towns depended on the mines they served or the infrastructure they were responsible for maintaining.

Some of the communities have completely vanished, while dozens remain as decaying buildings, crumbling ruins, or tell-tale bursts of colour indicating where cottage gardens once flourished. Some of Tasmania’s long-gone sites, as well as the stories behind their demise, are included below.

Ghost towns in Tasmania can be interesting to explore as they still have remnants of past eras of time in Tasmania’s history, moments where life was very different to how it was today. They often show a working class heavily focused towards mining and hydroelectricity industries which supported the economic and infrastructure growth of Tasmania.

Mathinna

Mathinna evolved to be one of the island’s largest towns when the gold rush to Tasmania’s north-east gathered traction in the 1890s.

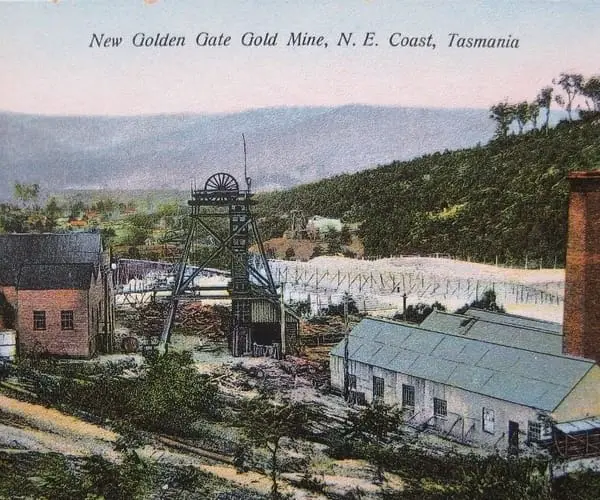

Like many others, the Mathinna goldfield began with the finding of alluvial gold in Black Horse Gully. The New Golden Gate, one of Tasmania’s largest gold mines, produced about 260,000 ounces (8 tonnes) of gold in total (historical) production. The area is littered with abandoned mines, prospects, and ancient workings, and it’s primarily crown land, so it’s rather easy to get around. The wilderness is very open and simple to stroll through, unlike other parts of Tasmania, however the hills are steep.

Prospectors fanned out after the finding of gold in Mangana in 1852, hunting for alluvial gold in adjacent locations. The entire terrain between Mangana and Mt Arthur was considered gold-bearing, and it wasn’t long until gold was discovered at Black Boy Plains and Reedy Marsh, as the area was dubbed at the time. It wasn’t until 1872 that the name Mathinna was formally adopted.

Mathinna evolved to be one of the island’s largest towns when the gold rush to Tasmania’s north-east gathered traction in the 1890s. William James Mullins, a farmer, was one of the prospectors. Mullins left home on June 20, 1913, to check possum traps and never returned.

His body was recovered two weeks later in a wooden funeral pyre, but his killer was never caught, and his death remains a mystery. Mathinna began to empty after the murder and the gold rush ended.

Only approximately 200 individuals remain today. This number is higher than many other ghost towns in Tasmania, however some of these people are located in farms on the edge of the village. Once you drive through and see the remaining buildings and remnants of a much busier town, you’ll feel the ghost town vibes.

Crotty

On June 5, 1900, the town reserve was officially inaugurated. In November of 1900, the town survey was finished. By 1902, the town had grown to about 150 homes with a population of 700 people.

The settlement had a smelter and railway connection with the North Mount Lyell mine at the start of the twentieth century.

Despite attempts to remedy faults in 1901 and 1902, the North Mount Lyell smelters failed.

In 1903, the Mount Lyell Mining and Railway Enterprise bought the company.

Crotty’s links with Gormanston, Linda, and Pillinger (Kelly Basin) were serviced by the North Mount Lyell Railway, which lasted in service for a number of decades before closing.

The smelters, hotels, and very small houses/huts are depicted in most historical images of Crotty. The most famous shot is from Geoffrey Blainey’s 1902 book The Peaks of Lyell, which was taken from the embankment immediately east of the railway line, looking west, up the main street, with the smelter smoke in the air and Mount Jukes in the distance.

In 1928, the last of the residents left.

Poimena

Poimena was once a busy town on Tasmania’s enormous Blue Tier Plateau, which is located in the state’s north-east corner. Poimena was founded by tin miners in the late 1870s, and by the 1880s, it had a school, stores, and a well-known hotel. Chinese tin miners were among the population, with about a thousand living and working in the area at the time. Today, an open field stands where their homes once stood, but the foxgloves planted by Chinese miners more than a century ago can still be seen, and markers indicate key parts of the ghost town’s important monuments.

Darwin (yes there was a Darwin in Tasmania)

Darwin was a small and short-lived settlement on the West Coast Range’s eastern slope of Mount Darwin.

On the North Mount Lyell Railway, which operated between Pillinger and Gormanston, it served as a rest stop.

Its post office was established on February 21, 1900, and was closed in 1903.

It was the site of Darwin Glass’ first discovery during the railway’s construction, as well as the subsequent work to locate and identify the Darwin Crater 60 years later.

Waddamana

Waddamana is an Aboriginal word that means “noisy water,” which is fitting given that it was the location of Hydro Tasmania’s first power station. Waddamana, in the heart of Tasmania, was founded in 1910, when workers began harnessing the waters of the Great Lake and Shannon River to generate electricity to Hobart. The last of the power plants was shut down in 1994, and they have subsequently been turned into museums. Some of the old cottages may still be seen in Waddamana village, lying next to empty plots of land with daffodil-lined paths leading to long-gone front doorsteps.

Tarraleah

During the 1920s and 1930s, the site was cleared as part of the area’s hydro development. The workers were initially housed in tents and simple shelters. Then, in the late 1930s, more permanent dwellings were built on the escarpment, planned as family homes in order to attract the enormous number of professional engineers and tradesmen needed for the Hydro project. The Chalet (now the Lodge) was also built in the same year. The Chalet was created to welcome visiting Hydro Engineers and Company Directors and was the focal point of the Tarraleah.

The village expanded over time, with more roads, houses, and public facilities being built, including churches, a town hall and picture theatre, public house, grocery, hospital, roadhouse, and more. The village’s population rose to several thousand people until the 1980s and 1990s, when capital projects in the area were completed and the populace moved on to other projects across the state. The town eventually closed down, and parts of the remaining structures were leased to short-term companies. The town was purchased in 2006 and rebuilt into what it is now, a village-scale hotel.

This new lease of life has been great for Tarraleah which could have suffered the same fate as many other ghost towns in Tasmania. The original homes and lodge have been tastefully preserved and the original long steel water pipes which run down the hill are still there. It’s a great place to stay, catch a glimpse of the past and enjoy the beautiful surrounding wilderness.

Adamsfield

The discovery of osmiridium, or “black gold,” in 1925 gave birth to this now defunct town. The natural alloy was seven times more valuable than gold at the time. Hundreds of miners were attracted to the area, but life was difficult – just getting to town took a 35-kilometer hike. The majority of the people lived in tents and survived on damper, tea, bacon, and tinned meat. It is now accessible through a two-hour hike from Clear Hill Road in the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area or by 4WD vehicle with a permission.

Pillinger

The desolate town of Pillinger, once a bustling port but now reclaimed by the forest, is located inside the World Heritage Area. The population exploded after the North Mount Lyell Company, founded by James Crotty, built a railway here. Residents were kept busy by three wharves, a saw mill, brickworks, and a shipping terminal, but after Crotty died, Pillinger vanished. A four-hour return walk along the railway and river, starting at Kelly Basin Road south of Lynchford, can still take visitors to the ruins at East Pillinger.

Linda

The abandoned village of Linda, where the skeleton of the Royal Hotel still survives, is a short walk from Gormanston. Linda was the terminus for the company’s railway line to Pillinger, which supported the now-defunct North Mount Lyell Mine. It was renowned as a tough town, and it was the scene of a brawl between Italian immigrants and locals known as ‘Britishers,’ in which one man was fatally stabbed.

Gormanston

One of Australia’s biggest mining disasters devastated the prospering town of Gormanston in western Tasmania in October 1912. A fire at the Mount Lyell copper mine killed 42 miners and imprisoned another 100 until the fire was put out. The population of the town, which had previously numbered in the thousands, began to dwindle. The school, the fire station, and several homes were were destroyed by cyclone-force winds in 1951. Gormanston had only six residents in 2013.

Lake Margaret

Tim Adams, the final resident of Lake Margaret, left in 2009 after living alone for 18 years for Hydro Tasmania, maintaining the old King Billy-pine pipeline. Lake Margaret was founded when the Mount Lyell Mining and Railway Company built a hydro-electric plant to power copper smelters in nearby Queenstown. It has the highest yearly rainfall of any Tasmanian municipality. The pipeline was shut down in 2009, and the town lawns are now encroaching on the forest. The power station, which is now a museum, can be visited.

Williamsford

The 500m-high Hercules haulage system that spanned more than 1.5km from the town up to the mine on the slopes of Mt Read was Williamsford’s defining feature. It was a 100-person town that was regarded as lovely because of its rocky and wild nature, but it was secluded. The Hercules Mine closed in 1986, and the region has been abandoned since then, although the haulage system’s ruins are still visible.

Dundas

Dundas shrank from a population of 1000 in 1891 to 300 in 1901. The Zeehan and Dundas Herald began reporting on the “deserted township” in 1895. The collapse of the Tasmanian Smelting Company signalling the end of local mines, resulting in the layoff of many people. With the growth and fall of mines, the town’s fortunes fluctuated over the decades. Today, the reddish crystal that is Tasmania’s mineral emblem is harvested from a thriving crocoite mine.

Boobyalla

During the second half of the nineteenth century, Boobyalla was a shipping port on Tasmania’s north-east coast. Coastal vessels brought tin from the adjacent Mount Cameron mines on a regular basis to the port from other Tasmanian ports.

The Boobyalla Post Office was established on July 29, 1875, and closed in 1927. Buildings such as the historic hotel and residences were either burned destroyed by bushfires or removed, leaving Boobyalla as a ghost town. At the mouth of the silted-up Boobyalla River, remnants of the old wharf may still be seen. The entire land is currently owned by a single property, with the main house at the end of historic Hurst Street.

Lottah

Around 1875, tin was discovered in Lottah, a small town in Tasmania’s northeastern region, Pyengana is the closest town. In 1880, the Anchor Mine began operations, and the village of Lottah sprang up around it. It had several hundred residents at its peak, with a school, two hotels, two churches, a bakery, and a football club among the community’s amenities. Lottah had a tiny Chinese community, and Senator Thomas Bakhap, who had a Chinese stepfather and served as an interpreter, was one of its more renowned people. Architecture professor Brian Lewis and RAAF commander Alan Charlesworth were both born in Lottah during its peak. When the Anchor Mine closed in 1950, the town’s population had been steadily declining for decades.